As an online personal trainer, I often meet people who have been through many cycles of activity vs complete inactivity.

This may sound familiar. It’s very common and may be due to any number of reasons outside of one’s control. From interruptions to your schedule, periods of stress and overwhelm or even an illness or injury. Regardless of the initial cause, getting back into the habit of exercise can be very challenging.

Why consistency is crucial

But it’s crucial because the longer we stay inactive, the more we stand to lose. Unfortunately, the human body isn’t the kind of asset that you can store away and return to later and find in the condition you left it.

Let’s say you treated yourself to a classic car or a piece of art that you’ve always wanted. You could lock it up in a garage or a vault for a year, and as long as it’s been left in a good spot, when you return to it, it’ll be in the same physical condition, not only that but if you’ve chosen wisely, it might even have increased in value.

Unfortunately, the human body doesn’t work like that.

The way inactivity plays out physically might be best phrased as ‘That which we don’t use, we lose’ and that’s down to the natural law of entropy, acting on us all equally.

If we go into sustained periods of inactivity, the law of entropy sets in and we stand to lose ground on performance, lose hard-earned muscle, and could even elevate our risk of more serious health issues.

All of this means you really ought to try to avoid your activity level ever dropping to zero at all costs.

When times get tough, and you can feel the grip on your exercise regime slipping, my advice is always to establish what we might consider a ‘fallback’ position, i.e. a base or minimum level of activity that you will still maintain, even if circumstances dictate that you have to deviate from your full training program. Another way of saying this would be that you should establish, respect and maintain your ‘fundamentals’

Having a strategy in place to ensure you maintain at least a minimal amount of activity will help you avoid losing a lot of the health, fitness, muscle and even mental health progress that you’ve worked so hard for. Because when you allow things to go to nil is when you stand to take all of the heavy losses.

Establish your baseline activity level

The great news here is that it likely doesn’t take anywhere as much exercise as you think it does to sustain progress. Indeed, many of my online personal trainings get better results in fitness, when they exercise less and eat more. So Often this is where a level of accountability coaching might be beneficial to help you stay on track.

Of course, this ‘fallback’ position is something that can be established as best practice in the future. But what if you’ve been out of training for some time and need to return to exercise now?

The first thing to note is that you shouldn’t try to return to the same level of performance as you were at your peak. You have to acknowledge that due to the lack of activity, you are at the very least temporarily de-conditioned.

Your strength, fitness and perhaps even range of motion is likely to have reduced over time, and that is entirely normal.

You’ll be able to get this back before long so don’t worry too much about it. It just wouldn’t be in your best interest to try to jump back in at the level you were working at previously. Because you’d be inclined to compare yourself to your previous performances, you might also be in a different place lifestyle-wise as far as healthy eating, sleep quality and stress any of which might have temporarily raised your likelihood of injury.

How to begin your return?

Getting in two of these workouts would be the ideal ‘on-ramp’ to higher intensity training and resistance training.

In addition to a noticeably different performance, you’ll experience more muscle aching than usual when returning to exercise which is why we’re starting with the type of exercise less likely to cause this.

Again, this is normal and, unfortunately, just par for the course.

You can offset some of this soreness and try to speed recovery by staying hydrated, keeping mobile and engaging in recovery practices like massage, Epsom baths, cold showers and sauna.

You should find that this muscle soreness begins to become less frequent after 7-10 days.

If the gradual reintroduction of exercise sounds quite slow and you can’t resist the urge to jump right back in, you will find that you will be hit harder by fatigue and muscle soreness.

It could be argued that you’ll be through the worst of the storm quicker too if you were to ramp up the higher-intensity workouts more quickly, but it’s important to take an honest appraisal or get a personal trainer’s opinion of your current condition to establish whether you are in a good place to weather such a storm. Indeed, an experienced personal trainer would be able to create a custom exercise program for you, so that you could be sure everything was well-calibrated.

I personally don’t recommend the ‘shock and awe’ route. If you’re considering it, you might benefit from reflecting on whether you are in the right place to recover from such a short, sharp shock or whether it is a betrayal of an all-or-nothing mindset that may or may not have contributed to needing to make a return to exercise after some time off in the first place.

Return in a way that acknowledges the cause of your lay-off

It’s one thing if you just lost momentum with your training or lost interest. But if the decline of your exercise practice was influenced by lifestyle factors that were making it harder and harder to find time for or have energy to implement that needs to be considered.

In particular, if stress or sleep deprivation were factors, then my advice would be not to come back with full intensity. Fatigue and overtraining are real things, so it could be a false economy. I wrote some notes on how to spot signs of overtraining for Athletics Weekly which you can read here.

It’s easy to make the mistake of thinking that results in fitness have a positive linear relationship with the amount of work put in, i.e. the more exercise you do, the better results you’ll get. Unfortunately, as with many things related to health and fitness, it’s a lot more nuanced than that and the only linear relation you are likely to find in fitness is that the more consistently you exercise, the better results you will achieve, which is a very different opposition than simply doing as much as you can.

Exercise drives change in the body. If you tax your cardiovascular system you get fitter, if you lift heavy weights you get stronger and build muscle – but these aren’t treats for the body, these are stressors.

You’re only getting fitter and stronger because you’re putting your body through stress, and the genius that is the human body responds essentially by saying to itself “Okay, well, if we’re going to be doing that again, we’d better get bigger, stronger, fitter etc”.

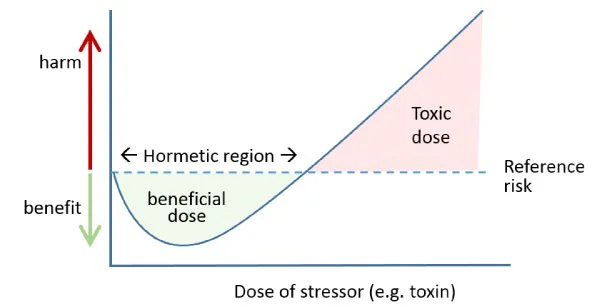

Exercise is a form of whats known as a hormetic stressor, which is something that causes temporary stress in order to force a positive adaptation in the body. There are numerous other examples of hormetic stressors we could use as part of a health and fitness regime, including (but not limited to) heat exposure, cold exposure and fasting.

Despite the benefits of these hormetic stressors, if you put your body through too much stress, which includes too much or too vigorous exercise and aren’t able to fully recover from it, you will get fatigued, and possibly even lower your immunity, on a long enough timeline you will face over-training and it will temporarily force you out of regular exercise and that’s the exact opposite of what we’re looking to achieve.

Recovery is crucial to a good exercise routine, so if you cannot get adequate sleep and rest or you do so much exercise that it’s just a bridge too far, this is when you run into problems.

My advice to avoid this would be to come back to exercise somewhere between 50-60% of what you used to do or think you’re capable of.

For example, if you’re used to doing 4 sets of bench presses at 60kg, come back with 2 sets at 30kg, if you’re used to running a 10k at a good pace, jog a 5k in at half the speed.

This keeps things from getting too complicated and it’s an excellent rule of thumb to follow. Do this for 2-3 weeks and then slowly build up to where you were previously and beyond.

This allows your body to adjust appropriately to the new stimulus. It won’t be long before you’re conditioned again and able to consider progressively more challenging training loads.

Recovery is just as important as training

As mentioned above, recovery is an important part of any training regime. Initially, it’s a great idea to build in active rest days on a 1:1 ratio with your actual workout days. So for every day you have a full-on workout, you have a day off afterwards.

This ensures that there is an adequate recovery built into the regime from the beginning, and to really maximise your time, I’d recommend ‘active rest’ days, rather than days of complete inactivity.

An active rest day can actually facilitate muscle recovery and would typically involve pleasure or hobby pursuits like walking, cycling, yoga or light sports like a friendly game of tennis.

The idea is that our bodies are built and intended to move, so you don’t want to go into an idle state just because it’s not a structured workout day, that’s a little too rigid.

To achieve a holistic approach to wellness it’s a good idea to maintain a distinct balance between training and activity.

The nuance is that workouts should have an intention behind them. For example, you do ‘Exercise A‘ to force an adaptation to see ‘Benefit B‘ – the stressor forces the change and needs to be recovered from, whereas activity is low impact, low demand movement or fun and offers no significant barrier to recovery, which means you can do as much of it as you want to.

View your lay-off as an opportunity

It would be remiss of me not to address the silver lining and point out the opportunity a long layoff represents, which is that in a temporarily de-conditioned state, you are primed for adaptation.

Your body gets used to what it’s exposed to, and this is actually why a lot of people get frustrated with their lack of progress with workouts, they simply don’t vary them enough to give the body any reason to adapt.

We have evolved to be survival machines, which means the body doesn’t waste energy unnecessarily. So you have to keep exposing it to progressive, but controlled strain, known in fitness as progressive overload. We call this process over-reaching, and it’s a tightrope to walk in order to avoid it becoming overtraining.

This way we continually deliver enough stimulus to force adaptation. As above, the body is basically saying to itself “Well if you’re going to keep doing this really hard stuff, we’re going to have to get bigger, stronger, fitter in order to comfortably handle the load or it might eventually pose an existential threat”

So coming off of a layoff, you’re going to be in a perfect position to see fast progress, it’s not uncommon to see positive recomposition at times like these, but you need to balance that relationship between overreaching and overtraining, which is where enlisting the input of a coach can help.

The pointers above should address the physical side of making your return to exercise, but we should also look at the reasons why you are here having had unplanned time off and needing to make a comeback, because moving forward you want exercise to become a consistent habit.

Again, you must take an honest appraisal about what led to the layoff in the first place, otherwise, you won’t know what the potential threats, catalysts or triggers might be for it to happen again.

The most important thing is to not be overly critical of yourself about the break from training.

Of course, it’s one thing if you were ill or injured, but if life got in the way or your discipline failed you, don’t dwell on things. Identifying the catalyst and taking ownership of the situation is key to getting past it and avoiding it happening again.

If you start to notice any destructive patterns kicking back in, address them, nip them in the bud and make the necessary changes. It’s all part of creating a positive mindset for fitness.

Success with health and fitness is all about consistency, avoiding setbacks, creating a realistic and sustainable plan, and then carrying out the program with as few missed workouts as possible.

Work to Create Sustainable Habits

To conclude, the slow and steady approach might feel a little frustrating at first, but it’s the prudent way to go.

Getting injured, overly fatigued or trying to come back at peak level could all lead to additional time out, so resist the urge to overdo it, get your initial conditioning under your belt and then keep building on it.

Your goal is to use these sustainable habits and never to have a long period away from exercise again.

Of course, everything is easier with a personal trainer in your corner, so if you would like to discuss how I might be able to help you make a return to regular exercise please feel free to schedule a consultation call here or indeed if you would like to take some time to research and determine the best online personal trainer for you, I have created a full buyers guide to assist you in making your decision.